Shells, snails and fossils – the beginnings of exploration

In the 18th century, coal was sought in Gams, probably because of the ever-increasing need for fuel. Because of the coal deposits, the clay marls were studied by the most important geologists of their time. One of the most famous explorers of the chalk deposits in the 19th century was Augst Emil Reuss, first professor of mineralogy in Prague, later in Vienna. In 1854, Reuss described the Schönleiten strata (slope area near the Akogel). He cited shells of fossil shells and snails that he had collected from a mine dump near the Gallerbauern (farmstead in the north of Gams). A plant find that Franz Ritter von Friedau had brought to his professor at the University of Graz, Franz Unger, probably also came from here. Unger was one of the leading researchers of the fossil plant world of his time. To acknowledge the interest of his student, he named this find Delesserites friedaui in 1852. Mention should also be made here of the find of Trinkerite reported by Julian Niedwiedzky in 1871. This is an amber-like fossil resin that has a high sulphur content.

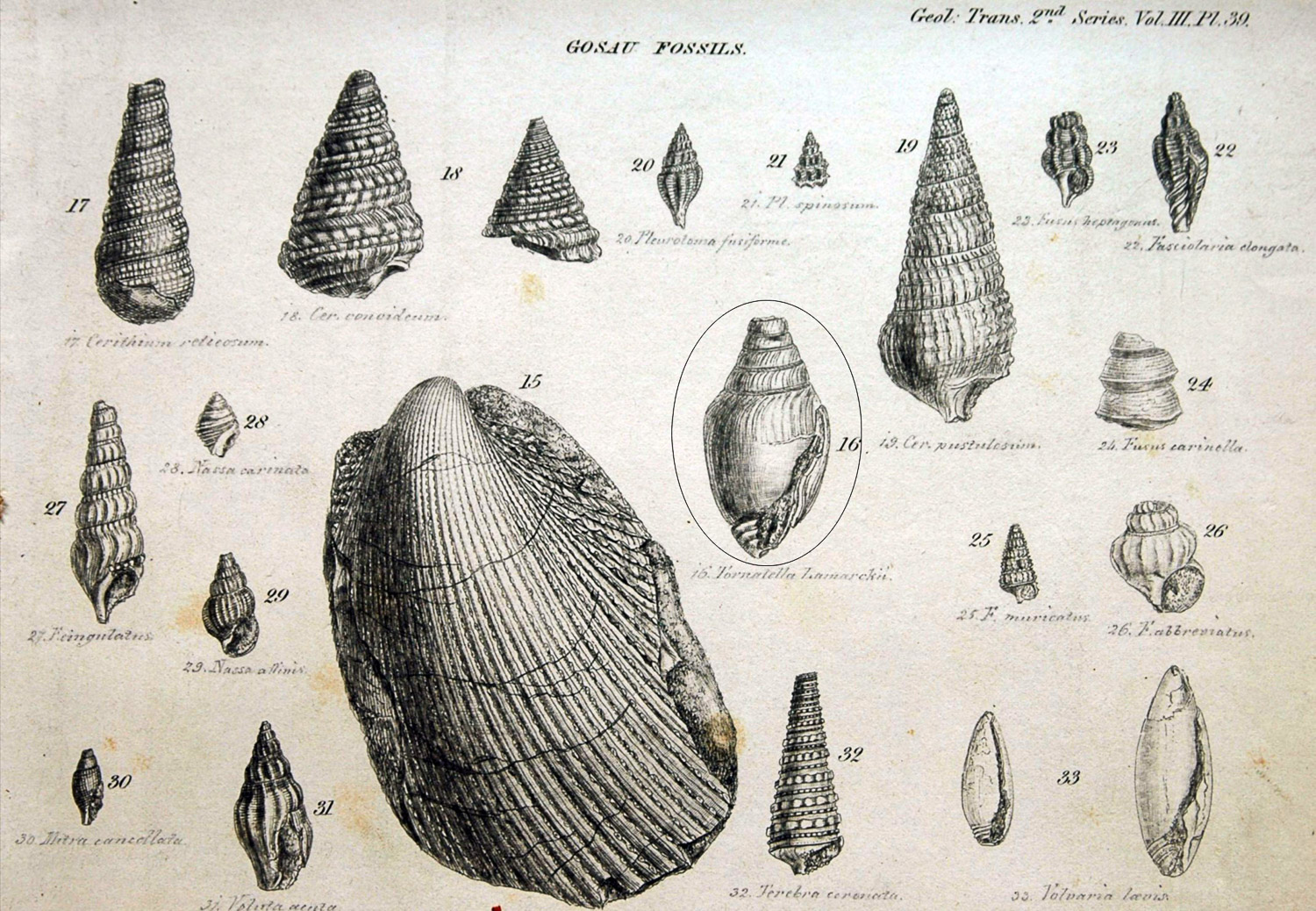

Several types of fossil shells and snail shells from Schönleiten have found their way into science. Friedrich Zekeli had already examined the fossil snail shells from here in 1852. Moriz Hörnes, who worked at the Court Mineral Cabinet, described a form from the Schönleiten Reuss in 1855 in honour of Purpuroidea reussi. Today it is called Megalonoda reussi. It had large nodules and is one of the most striking forms from Cretaceous deposits in the Eastern Alps. In 1854 Karl von Zittel described the shells of the Gosau layers. Zittel had also written this treatise as an employee of the Court Mineral Cabinet. Later he became professor of palaeontology in Munich. He published extensive works on fossils and is considered the most important palaeontologist of his time.

Interesting finds are still coming to light today. The jaws of a fossil fish were found during collections by the Vienna Museum of Natural History at the bend in the Akogelstraße above the swimming pool. Like paving stones, the teeth covered the entire mouth of the fish. With their help, it ground up the hard lime shells of mussels and other animals to get at the nutritious meat. Ortwin Schultz from the Natural History Museum in Vienna and Maja Paunovic from the Geological Institute of the Academy of Sciences in Zagreb found out that it was the species Coelodus plethodon. Besides chamois, it was previously only known from as far away as Portugal and Niger.